Login

A Comparison of Communist politics in the Nordic countries in relation to the so-called Moscow-line

written by Torgrim Titlestad

posted date 22.08.2023

Previously not published.

Based on a lecture given at a conference on Nordic Communism, Copenhagen 20th of January 2002.

Generally it should be possible to apply the method for the whole period 1919–91, taking into account the variations between the different periods:

1st period: 1917–1929 – The CPSU as a party governed by oligarchs

2nd period: 1929–53 – The CPSU as a party governed by one leader, J. Stalin

3rd period: 1953–91 – The CPSU as a party governed by a so-called collective leadership

I want to underscore the fact that the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943 was primarily a formal question of changing from mainly a kind of multilateral and secret connection through the institutions of CI to an even more secret and unilateral connection between the upper institutions of the Soviet party and each Communist Party. As Robert C. Tucker puts it: "The Comintern did go on actively existing in another guise and. The dissolution was indeed a manoeuvre to cover up the impending use of the foreign Communist parties as tools of Moscow in the empire-building process and international affairs".[1] The most striking change after 1943 was that Stalin was given a freer hand to personally deal with the different CPs than before, the Soviet CP during this period meaning more or less J. Stalin in person. After the "emasculation" of Comintern, Dmitri Volkogonov writes, "Stalin resorted to strictly totalitarian methods in international and Communist affairs. Secret deals, toughening the NKVD's agencies at home and abroad... became his preferred style of 'revolutionary activity', especially after the formal dissolution of the Comintern in June 1943".[2]

Access to the Moscow archives in the 1990s

Until the selective and partial opening of the Moscow archives[3] in the 1990s it was difficult to empirically establish what the decisive factors were in the formation of the politics of a CP and what their relations to Moscow really amounted to. Completely new and more complex angles of analysis became visible after the Moscow files were made available in the 1990s:

1. The Soviets presented themselves not as a monolith but as a collection of different institutions (e.g. The International Department) with personalities hitherto unknown in the West.

2. There were competing views within the CPSU and pragmatic considerations that were taken into account in the Soviet apparatus, concerning the different CPs.

Suddenly a multitude of sources existed compared to the previous years. However, most of us were aware of one important but missing link: the archives of the secret services of the CPSU and the files of Stalin which were still mostly locked up and inaccessible, with some rare documented exceptions.

Where are the conceptual and theoretical tools in Nordic Communist studies?

Too many historians have continued to develop their Communist studies as before and have still not made the underlying conceptual framework of their analysis explicit, which by now they should have done – and reflected upon. During the period of the Cold War two main rival conceptual or theoretical models were used by historians in the West:

1. The Totalitarianist school: Communist parties are totalitarian parties with one ruler and a ruling elite at its apex. Party opposition exists only for a short time – until the dissident either leaves the party himself or is expelled by the leadership. Thus a Communist Party continues to be monolithic both from without and within. Wherever you look in the party pyramid you will, more or less, find the same uniform and homogenous politics channelled through different personalities.

2. The Comparative school: Communist Parties are usually dominated by the Soviet Communist Party, but they contain different political currents dating back to the twenties during the lifetime of Lenin and these diverse currents express national/cultural/personal differences. To understand the political dynamics of each party you have to use the so-called indirect research strategy: at first you have to know the policies in the CPSU-leadership and then analyse the politics of each national party (comparison). The origins of this analytical concept are to be found in the 1956 reformist changes from within the CPSU - with the condemnation of Stalin's crimes: how could the CPSU change from within without containing reformist political cultures under the monolithic surface – before 1956?

A necessary question thus has to be asked: where do we stand conceptually as scholars before we start to carry out our work on Nordic Communism?

If we realise that the Communist movement has a hidden life with different political currents and, consequently, cryptopolitics within the monolith - seemingly boring official speeches by Communist leaders may be read in a new light, as William McCagg Jr., one of Stalin's biographers, wrote already in the 1970s:[4]

"It goes without saying that one has to read between lines, to follow hidden ideas, And this reading between the lines is not illegitimate: on the contrary, the texts are constructed in such a way that reading between the lines is the only way to grasp their meaning... Those who cannot read between the lines are as naive as little children."

I think this postulate, even if it was written before we got access to the Moscow archives, has something substantial to remind us of, before we plunge into the task of writing our Nordic Communist history. It is confirmed by Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov in 1996: "Knowledge of the Russian language is not enough: one needs to read between the lines of the most secret documents - to see and feel as those who had produced them and consumed them".[5] Have we sufficiently taken advantage of that method of analysing the Nordic parties – available before Glasnost and Perestroika? Have we, sufficiently, consulted oral sources in the face of a lack of written sources to verify and clarify the secret contacts between the CPSU and the national parties?[6]

New perspectives for analysing the Communist Parties

Personally I have preferred the second analytical approach, the comparative school.[7] But even this methodology needs to be reviewed after access was given to the CPSU-archives. The archival sources have given clear evidence/documentation of the existence of three important processes:

1. The CPSU tried to govern the politics of the different CPs mainly through the CP General Secretaries.

2....through the use of Moscow gold since the 1920s until 1991.

3....and through secret channels (secret services).

The structure of the Communist movement also became clear: it was a pyramid with the CPSU General Secretary at the very top, especially in the years 1929–53. The Communist movement was ruled as a modern fiefdom with the Soviet leader as the feudal lord, or if one prefers another analogy – as a multinational corporation with the Soviet leader as the general director. The unofficial, unwritten rules of the Communist movement were often more important than the official ones. en/index.htmladmin

Due to the lack of contemplating what consequences the new sources would cause for the conceptual approaches and paradigms used in Communist studies, most historians hurried to Moscow to verify old personal positions after access was given to the new files. Unfortunately, most historians continued to use documents and analyse their contents as before.

One of the most remarkable results of the preliminary studies of the documents, however, was to discover the indirect and secret Soviet control of the CPs and raised the need for further research along the following lines:

1. Closer analysis of the CP leaders' biographies and their changing power.

2. Closer monitoring of the political consequences of Moscow Gold (corrupting national CP politics by buying its politics and some of its foremost militants, cf. Lars Björlin[8] and Morten Thing[9]).

3. Clarifying of the role of Soviet secret services in the CPs.

An alternative periodisation of political phenomena in the different national Communist movements can also appear: the time that a political crisis surfaces in a CP does not necessarily mean that it occurred as a direct result of the actions of the visible actors and the specific arguments used at that actual moment. On the contrary it is sometimes necessary to speak of a crisis caused by careful and secret operations that were initiated or exacerbated by Stalin years in advance, surfacing only because Stalin did not get it his preordained way. Stalin was not automatically victorious...

The importance of secrecy in the Communist Parties

Already before the 1990s important work was done by Niels Erik Rosenfeldt who went to the core of the problem: the secret apparatus of Stalin and its role in the CPSU and in foreign CPs. Rosenfeldt's main ideas in this field were verified by the opening of the Moscow archives.[10] Until now almost nobody has tried to map out the substantial political and organisational role of this apparatus with respect to the Nordic CPs, as Rosenfeldt points out – many Western historians have either tended to ignore the problem of the secret departments and special sections altogether[11], or attached no great importance to them.[12] With the launching of the Nordic project on Communism we shall commit a fundamental error if we do not thoroughly conduct this kind of analysis: the role of the Soviet secret services in the politics of the Nordic CPs. As the Russian historian Irina V. Pavlova concludes: "The task of realising the special 'underground' character of Stalin's power, however, constitutes to this very day a serious challenge..."[13] Without this kind of analysis, we can forget the project being a scientific project.

I started by saying that the archives of the Soviet secret services have been more or less closed even after the general opening of other Soviet archives - how can we then carry out this kind of analysis? We have, in spite of the sparse sources in the field, got some clues that help us understand how Stalin secretly acted towards the Communist leadership in foreign countries. One such important documentation is the former secret conversations of Stalin and foreign CP leaders[14], especially between Stalin and Thorez in 1944 and 1947.[15] As Volkogonov states: "In private he laid down the law, lectured and hectored, and told his vassals how to act and how to lie".[16] We then have to ask: what were the tools used by the Soviets to control each CP - and how can we describe how they acted? Of course they vary from period to period, but we can identify some elements.

The unofficial tools of control that Stalin possessed

From 1931 and onwards Stalin played the major top role in the Communist movement, trying to establish the Communist world movement as a totalitarian movement. He achieved quite a lot in this direction before WWII, through the Moscow-processes (purges and trials), either by killing his potential and real opponents or terrifying the others. If we study the methods of Stalin we soon observe an important feature: his focus of attention was not politics - the organisation was his prime target and object of concern. The first thing of importance for him was the control of the organisation and its so-called monolithic unity. In this field he also defined the terms of political and organisational discourse[17] as if they were originally derived from Karl Marx.

To secure his personal power he created the slogan that any political deviation from the party line represented a dangerous split in the party. He invented a special "beast" – the Trotskyites as party wreckers and creators of splinter groups. A comprehension of how this "beast" and other "deviationists" should be viewed and treated is most clearly given in the words of the Soviet chief prosecutor, Vyshinsky, in his summation at the end of the Moscow trials: "The 'bloc' of the Rights and Trotskyites, the leading members of which are now in the prisoners' dock, is not a political party... but a band of felonious criminals, and not simply felonious criminals, but criminals who have sold themselves to enemy intelligence, criminals whom even ordinary felons treat as the basest, the lowest, the most contemptible, the most depraved of the depraved... The whole country, from young to old, is awaiting and demanding one thing: the traitors and spies must be shot like dirty dogs. Our people are demanding one thing: crush the accused reptile!"[18]

A true Communist Party in the Stalinist theory is a party without factions and with a so-called collective leadership, based on democratic centralism. Seen on the basis of the new evidence from Moscow these Stalinist notions become ridiculous – they were merely a part of creating the myths of democracy and collective leadership in the Communist movement under Stalinist control.[19] This kind of party rhetoric was a theatrical manoeuvre to deceive CP members and non-Communists alike. When Moscow accused any Communist leader after 1930 of being dictatorial, not respecting collective leadership and democratic centralism etc, it would often be a signal that Moscow had identified a possible opponent to Moscow rule. This is the background to understanding Stalin's prime interest in the party organisation: the organisations keep the vestiges of power and define the politics. Therefore he decided:

1. To control the parties he gave himself the privilege of appointing and destroying General Secretaries (e.g. Paris/D. Manuilsky 1931).[20]

2. To establish party schools for foreign CPs in Moscow at the end of the 1920s: to develop new and "pure" party cadres educated to follow the thinking and instructions of Moscow (and simultaneously to recruit secret agents to the Soviet intelligence services) – he thus constructed the tools to control the CPs from within by nationals of the countries in question.

During the 1930s we can see how the CPs changed into becoming instruments for Soviet foreign policy, generally obeying the instructions from Moscow, and by this we actually mean instructions, e.g. the telegrams to NKP 1939–40.[21] We should also add another tool to our analysis: the Soviet diplomatic missions and embassies were also "stations" in the line of command from Moscow, conveying orders, money etc.

At the end of the thirties Stalin thus should have been pleased, as it was apparent that he had kept the control of the Nordic CPs in his hands:

1. He had got rid of most of the pre-1917 cohort of CP-leaders, educated in their national labour movement before the Russian revolution, either by killing them, expelling them, silencing them or making them his obedient adherents, often controlled through the stimulation of Moscow Gold.

2. He had established a new breed of Soviet educated leaders, mainly in the middle level – around in the districts of the parties, with an internalised Soviet and Stalinist loyalty.

3. He had developed the necessary tools to control the leaders at different levels: through his CP-contacts who were controlled by secret services – or by his "hidden hand".

The dynamic factor: World War II – as creator of new power networks within the CPs

The war 1939–45 changed the established external monolithism in the CPs. A lot of the pre-war leaders were executed by the Germans, imprisoned in German concentration camps, or lived in exile in Moscow. New and young recruits with virtually no previous experience in the Communist movement joined the parties and many of them were to fill the empty places of the killed or arrested leaders. The party grew for instance 10 times greater in Norway. The pre-war generation became a numerical minority within the parties.

In the first post-war years Stalin had to face this unexpected problem with a lot of new recruits and new networks outside his control. In 1937 he had sensed a kind of similar danger within the Soviet party, as Amy Knight writes: "He was outspokenly critical of party officials who cultivated a network of men personally loyal to them..."[22] Stalin disapproved of such networks and said: "What does it mean to drag along with you a whole group of friends? It means that you gain some independence... if you will, from the Central Committee".[23] The Central Committee was another word for his own personal power, and his method of solving his problem was to introduce more "intra-party democracy".[24] One party leadership which was hit by this accusation of dragging around a "whole group of friends" was the Furubotn-leadership in the Norwegian Communist Party. To a large extent Stalin's problem was: how to pave the way for a restoration of his pre-war organisational control and, consequently, unchallenged power in the CPs. His influence was temporarily limited by the international CP line: a national road to socialism was proclaimed to be possible for the European CPs.

Preparing for the Stalinist restoration

The CI institutions, official and secret ones, as well as the corresponding Soviet ones, have to be analysed during the years 1917–43 to see how the CPSU influenced the different CPs in this period. We also have to concentrate on the secret Soviet institutions and their channels of communication and influence to the different CPs after WWII. The Moscow files show us how the International Department collected information on the leaders in the CC of each CP etc, the existence of different groups in the party and its leadership, the shifting balance of power, how the CPSU might influence – especially through secret structures – the congresses etc.

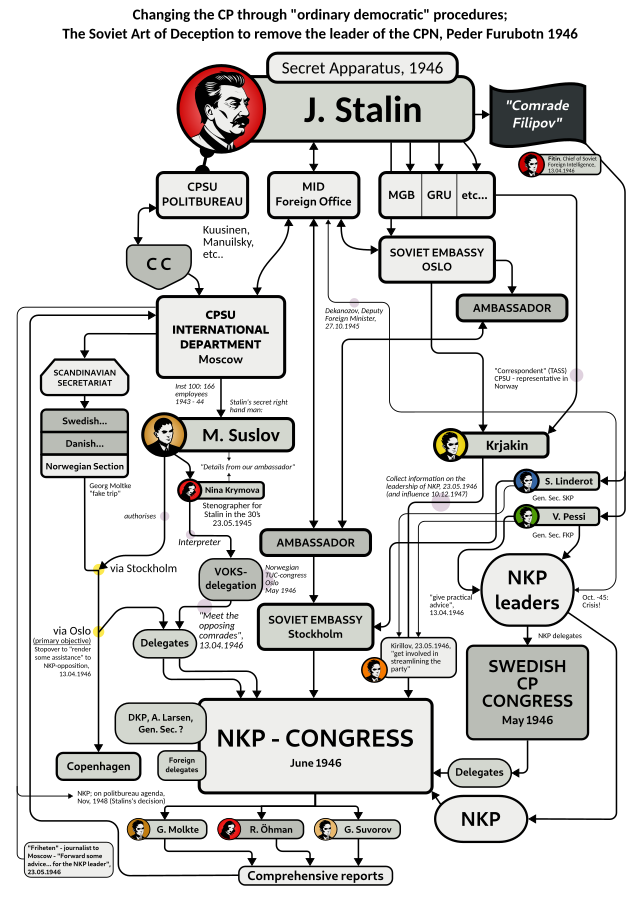

Changing the National Leadership of a CP through "ordinary

democratic" procedures. The Soviet Art of Deception

(Example - 1946 Congress of NKP: Diagram)

With this diagram it is possible to see how the CPSU treated the Nordic CPs as a whole. The CPSU used Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, Danish and Soviet Communists to promote its organisational and political influence in the one party (a modus vivendi that would not just have been used against the Norwegian party). It shows how Stalin carefully and secretly began to restore his power in the Nordic CPs after WWII.

The formation of Cominform in the autumn of 1947 is the first clear signal that Stalin wanted an official legitimisation for the restoration of his pre-war monolithism in the CPs, and a new Communist monolithism and the purges in the European Communist Parties after 1947 were the subsequent consequences. The minutes of the three conferences of the Cominform 1947/1948 and 1949 – now available – clearly demonstrates Stalin's intention of tightly controlling the European Communist movement and the International Department of the CPSU was one of his important tools in this process of restoration.[25]

Thus it should be self-evident that we cannot compare Nordic Communist politics without at least analysing how the different parties and their politics were treated through the International Department of the CPSU. We should also continue to try to gain access to Stalin's chancellery[26] and the secret files of the Soviet intelligence services, as we already have some evidence which proves that Soviet intelligence networks operated within the CPs.[27]

Conclusion

During the period of Stalin's dominance of world Communism he created certain parameters to control each CP, both through institutional and personal connections (through the Soviet CC or through Stalin's secret apparatus); methods of controlling the Communist Parties which it is assumed were inherited by his successors after 1953. We can see that Stalin's main focus was on the organisation and its monolithic character. If he identified a tendency that was working to form a distinct group within a party, his institutions gave him reports on those involved, their biographies (personal history going back to the 1920s), level of organisation, numerical strength etc. It is possible to see how Stalin, after a certain period of observation, arrives at a decision which he subsequently puts into effect through his various personal and institutional channels of power. Politics is not the object of his concern; instead he is mostly interested in the upper party echelons and those associated individuals and groups who could best serve his interests.

Briefly, it is almost impossible to compare the politics of the Nordic CPs without knowing the different attitudes of the Soviet apex towards each Nordic CP and how the CPSU continuously tried to influence and mastermind the organisation and the politics of each CP (of course the reactions of the personalities and organisations of each national CP should be considered before making any final conclusion). This kind of analysis should be given appropriate attention in our future research work. Until now we have not treated this problem with sufficient attention. The role of the secret Soviet rule of the Nordic CPs has to be a main issue of our study.

REFERENCES

[1] Robert C. Tucker, "The Cold War in Stalin's Time", Diplomatic History, 2/1997: 274.

[2] Dmitri Volkogonov, The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire, London 1999: 125.

[3] See an important article on the new sources by Kevin McDermott, "The history ofthe Comintern in light of the new documents", International Communism and the Communist International 1919-43, Tim Rees and Andrew Thorpe (editors), Manchester 1998: 31-40.

[4] William McCagg Jr., Stalin embattled, Detroit 1978: 23.

[5] Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov, Inside the Kremlin's Cold War - From Stalin to Khrushchev, London 1996: xii.

[6] See Torgrim Titlestad , Metodiske problem ved bruk av munnlege kjelder i studiet av kommunismens historie, I Stalins skygge Bergen/Stavanger 1996: 568-85.

[7] Ibid: 41.

[8] Lars Björlin, "Russisk guld i svensk kommunisme", Guldet fra Moskva - Finansieringen af de nordiske kommunistpartier 1917-1990, Morten Thing (ed.), København 2001: 64 - "The question is which possibilities the Swedish party leadership had to present an independent point of view towards the leadership of the world party when it simultaneously applied to the EC's budget commission for money to keep up its political activity".

[9] Morten Thing, "Kommunisternes kapital", ibid - 171: "The money was supposed to lead to the recruitment of more members and gather new readers. In stead it seems that the money was used to cement the party as a something by which one could make a living. Thus money becomes something very significant in the relationship between Moscow and the DKP - or whatsoever CP".

[10] Niels Erik Rosenfeldt, The importance of the Secret Apparatus of the Soviet Communist Party during the Stalin Era, Mechanisms of Power in the Soviet Union, Niels Erik Rosenfeldt, Bent Jensen and Erik Kulavig (eds.), London 2000: 42.

[11] See Richard J. Aldrich, The Hidden hand - Britain, America and the Cold War Secret Intelligence, London 2001: 637 - "Some historians have dealt with the issue of vast secret services activities during the Cold War by simply not discussing them at all".

[12] Irina V. Pavlova, The Strength and Weakness of Stalin's Power, ibid: 31.

[13] Ibid: 38.

[14] D. Volkogonov, op.cit: 129.

[15] Phillipe Buton, "L'entretien entre Maurice Thorez et Joseph Staline du 19 novembre 1944" and Mihaïl Narinski, "L'entretien entre Maurice Thorez et Joseph Staline du 18 novembre 1947", Communisme, no. 45-46, Paris 1996: 7-54. Norwegian commentary by T. Titlestad, "Komintern, Stalin og NKP", Historisk Tidsskrift, no. 1/1998.

[16] D. Volkogonov, op. cit: 129.

[17] Iver B. Neumann, Norge - en kritikk - Begrepsmakt i Europa-debatten, Oslo 2001: 26.

[18] David Jeans and Jane Jenkins, Years of Russia and the USSR 1851-1991, London 2001: 320.

[19] Ronald Hingley, Stalin - Man and Legend, New York 1974. When attacking adversaries in the CPSU from 1928 Stalin made adroit use of "democratic pressures": "Persistently advocating 'control from below'. 'Party democracy' and 'self-criticism', Stalin was disciplining recalcitrant little Stalins by invoking libertarian symbols..." - 192.

[20] William J. Chase, Enemies within the Gates? - The Comintern and the Stalinist Repression, 1934-39, New Haven/London 2001: 18 and 427 ("So predominant was the VKP's (CPSU) power and influence within the Comintern that its delegation often decided among themselves... who to remove from and appoint to the Central Committees of fraternal parties. They also determined who would attend Comintern Congresses...").

[21] T. Titlestad, op. cit. 1996: 122.

[22] Amy Knight, Beria - Stalin's First Lieutnant, Princeton 1993: 75.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] See The Cominform - Minutes of the Three Conferences 1947/1948/1949, Giulano Procacci and Grant Adibekov, Milan 1994. The book also contains important articles on the issue.

[26] See documents published by T. Titlestad in The Communist Chronicles - Studies in Communist History, Stavanger 2002, Fond 3, Opis 23, Delo 226, p. 13-28, 39-49 and Fond 56, Opis 1, Delo 1283, p. 180-87.(Grigoryan).

[27] See T. Titlestad, op. cit. ( Matvey Zacharov).